A new attempt to create a national, longitudinal health record was one of the big ideas in the 10 Year Health Plan. However, the use case and architecture is far from clear, and there are some big commercial issues to address with health tech vendors…

The NHS has a troubled history when it comes to national record and data projects. When the National Programme for IT was launched in 2002, it set out to develop a Summary Care Record that would make data available to clinicians wherever a patient presented for treatment.

England had never had a single database of patient information before, and concerns about security and access effectively scuppered the idea. In 2010, the SCR was scaled back to “hold only the essential medical information needed in an emergency.”

Four years later, NHS England launched the ill-fated care.data project, a plan to create a massive database of secondary and primary care information for planning, research, and commercial exploitation. Amid a huge outcry, and terrible public communications, the idea was scrapped the same year.

A big think tank has a big idea: and the government runs with it

This unhappy history has not put the idea of a single national record to bed. Instead, last summer, the Tony Blair Institute for Global Change argued the NHS should try again.

In a report, it argued the UK now has a “mixture of integrated health data sets.” These include the remains of the SCR, and the shared care records which have been developed over the past decade to improve professional access to health and social care at an integrated care system level.

Then, there are data and analysis platforms, including the Federated Data Platform, which NHS England is pushing hard. And there is the NHS App, which has gone through a decade of stop-start investment, while the use of commercial patient held records has gathered pace.

In its report, the TBI argued that what is needed instead is an “integrated, digital, longitudinal health record” to “act as a single source of the truth” and feed portals for care, planning and research, and patient engagement. Incoming health and social care secretary Wes Streeting embraced the idea.

At the launch of the public consultation that led to the 10 Year Health Plan, he pushed the benefits of a “patient passport” that could be accessed by GPs, hospitals and ambulances, while delivering “suitably protected and anonymised” data to researchers and companies to drive growth.

The 10 Year Health Plan duly featured the development of a ‘single patient record.’ However, it didn’t say how the SPR would be architected or set out a timetable for its development. And there is no mention of the idea in last month’s Medium Term Planning Framework, which sets out NHS England’s ‘to do’ list for the next three years.

But what is the use case?

Members of the Highland advisory board were not surprised that the SPR is missing from the framework. Ian Hogan, a chief information officer at a mental health trust, said it’s clear that the SPR is “very much a second phase” project, given the time it will take to clarify its use case, architecture, and funding.

David Hancock, an expert on interoperability, who has been attending industry events on the SPR, said NHS England has spent most of the summer on a “discovery” programme, to find out what different stakeholders might want from it.

This seems to have found that professionals, particularly those working in long-term and emergency care, want more information from other professionals to provide context for their patients; and patients want professionals to have data, so they don’t have to repeat their histories or end up in hospital when they don’t need to.

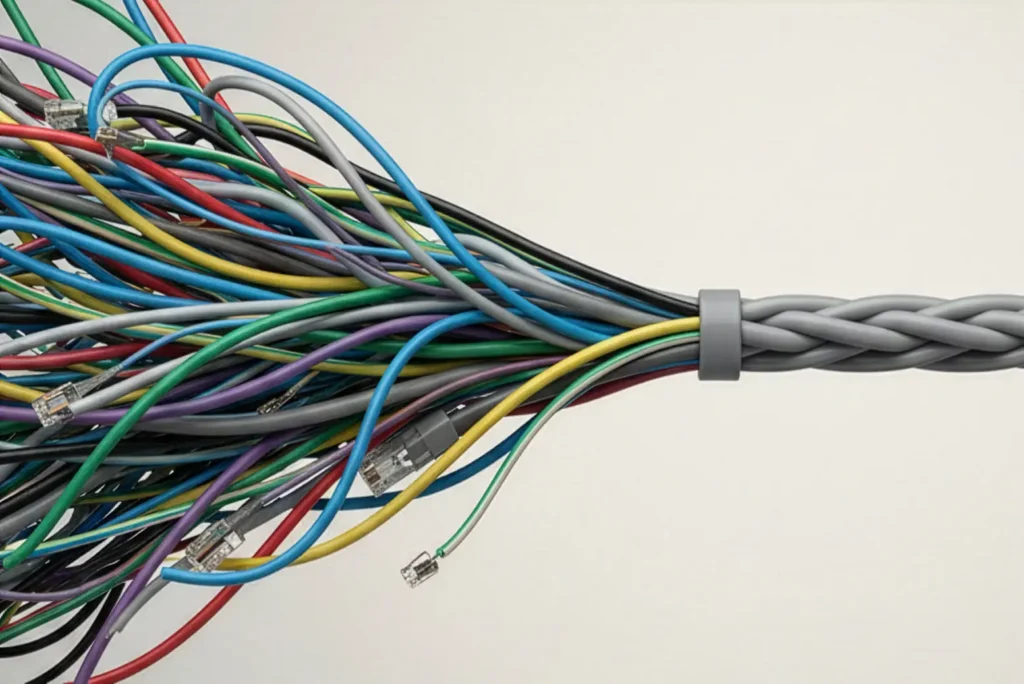

This, he pointed out, “is the benefit of a shared care record.” So, on the face of it, NHS England could deliver this at a national level “by joining up the 32 shared care records that already exist” fairly easily as long as it picked the right integration model.

Three prototypes

As things stand, though, NHS England is not doing this. Instead, it is developing three prototypes, using different models: a record with its own database; a record taking feeds from other systems (the approach taken by shared care records such as Interweave); and an Uber-style platform that pulls in ‘events’ data, but doesn’t persist it.

David Hancock suggested this might mean NHS England is starting to think about a different use case for an SPR: to support the NHS App. Andy Kinnear, a consultant who pioneered shared care records when he worked in the NHS, agreed.

“A lot of Wes Streeting’s agenda seems to be about making things better for patients; or at least giving them the same kind of consistent digital experience that we get when we use consumer tech,” he said. “It’s going to be hard for the NHS App to do that if the backend is 200 plus systems. It needs something behind it to create that consistent offer.”

What will the architecture look like?

An SPR to backend the NHS App might be useful. But it doesn’t sound much like the TBI’s all-singing, all-dancing digital health record. Nor would it necessarily deliver the direct benefits to care that are being delivered by the more advanced shared care records (like OneLondon, which has focused on care and end of life plans).

Nor would it automatically open up the kind of data that would persuade companies to offer the NHS “cut price deals on medicines” or “priority access to new treatments”, as promised by Wes Streeting. The advisory board found the lack of clarity about the purpose of an SPR frustrating, given the energy and resources that could be directed to it, when the NHS and its IT teams are under so much pressure.

But the real challenge will come when NHS England has to pick a model. “When this gets really tricky is when you say: how do we do the architecture?” said Andy Kinnear. “I think it would be madness to throw away the achievements of the shared care records, but history tells us that governments are always tempted by the idea of working with big companies on big databases.”

Details will matter

Advisory board members also noted that to build an SPR, NHS England will have to grapple with some of the practical issues that have bugged NHS tech projects for years. What standards will the SPR use to ingest and store data? How will its provenance and quality be guaranteed, so clinicians are confident to act on it?

What kind of security wrapper will it have? What will the access controls look like? Nicola Hayward-Cleverly, a former NHS CIO, consultant and non-executive director, pointed out that in some cases, access needs to be opened-up. The NHS App is still trialling proxy access for the families of frail elderly people, and the parents of children.

In other cases, it needs to be locked down. She gave the example of accessing the data of a serving member of the forces. “We need to work out how to get information out, securely, to where people happen to be, in the context they happen to be in.”

Entrepreneur Ravi Kumar said he has proxy access to the records of some of his elderly relatives in India. But then: “My relatives used to take their paper records to the hospital, and now they just hand over their phone number so anyone behind the desk can call them up. Would that be acceptable here?”

The historical reaction to the idea of a national shared care record, and the work that regional projects have had to do since to win support for their work “data field by data field, clinician by clinician, use case by use case,” as Andy Kinnear put it, suggests it wouldn’t be acceptable.

And it’s notable that the medical and privacy groups that opposed care.data and the FDP are already warning that Wes Streeting’s vision for the SPR will “unavoidably create a vulnerable database, the content of which can be shared with drug companies.”

Health tech companies will want to talk commercials

Another challenge is that an SPR will have commercial implications. David Hancock pointed out that, at some point, vendors may be told they have to integrate with the new record. “What happens when you find that some suppliers will do that quite happily and quite easily, but others won’t?” he asked.

“Do you pay them? Do you create infrastructure to make it easier? Do you support them if they need to re-platform their systems?” Various members of the advisory board pointed out that as things stand vendors can make it difficult or prohibitively expensive for third parties to integrate with their systems, slowing the exchange of information, and blocking innovation.

Imaging expert Rizwan Malik argued the NHS should just be tougher about this. “We should start from first principles, which is that we have lots of data locked up in siloed systems, so how do we unlock them?” he said. “This is our data. We should not allow suppliers to stop us using it.”

He also felt the NHS would be better off creating local, practical use cases for data sharing than going in for another big project, that might not get anywhere. In which case, the best role for government and NHS England would be to stop talking about policy and guidance and start talking brass-tacks on issues like standards and APIs.

Not a quick fix

Overall, the advisory board felt there is a need for clarity about the use case for an SPR, its architecture, and how the NHS and its suppliers will be expected to engage with it. Advisory board chair Jeremy Nettle said sorting out these issues will be possible, but it will not be quick.

“It will be possible to create a database, a data layer, or a backbone, but you won’t just be able to put it in,” he said. “It will take five or ten years.” Which will be well into the next Parliament: a lifetime in the rise and fall of big IT projects.